Pub/Sub Clearly Explained (in Under 6 Minutes)

(6 Minutes) | How It Works, Best Practices, Why Teams Reach for It, When Not to Use It, and Tradeoffs

Get our Architecture Patterns Playbook for FREE on newsletter signup. Plus, receive our System Design Handbook for FREE when it launches in Feb 2026:

Unlock Modern Search Inside Postgres With pg_textsearch Extension

Presented by Tiger Data

BM25 ranking, hybrid retrieval, and transactional simplicity all in one Postgres extension. Think Elasticsearch-quality relevance with native Postgres simplicity. No external search engine. No syncing pipelines. Just better relevance for RAG, search, and AI workloads.

Pub/Sub Clearly Explained

Pub/sub is not “just a queue with topics.”

It’s a different way of wiring a system. Instead of calling a specific service and waiting, you publish an event and let whoever cares react.

That shift sounds small, but it changes your scalability, your failure modes, and how teams add features without tripping over each other.

If you’ve ever added “just one more downstream call” and watched latency, coupling, and deploy coordination explode, pub/sub is the pattern that turns that mess into a cleaner fan-out.

What Pub/Sub Actually Is

Publish/subscribe (pub/sub) is a messaging pattern where publishers broadcast messages to a topic, and subscribers receive messages for the topics they registered to, without either side needing to know who the other is.

That last part is the real power: decoupling.

The publisher doesn’t care who listens, and the listener doesn’t care who produced the event.

Each side evolves, scales, deploys, and even fails independently. You stop wiring services together one call at a time and start letting events flow through the system like signals; allowing teams to plug in new subscribers without modifying the service that emits the event.

How It Works

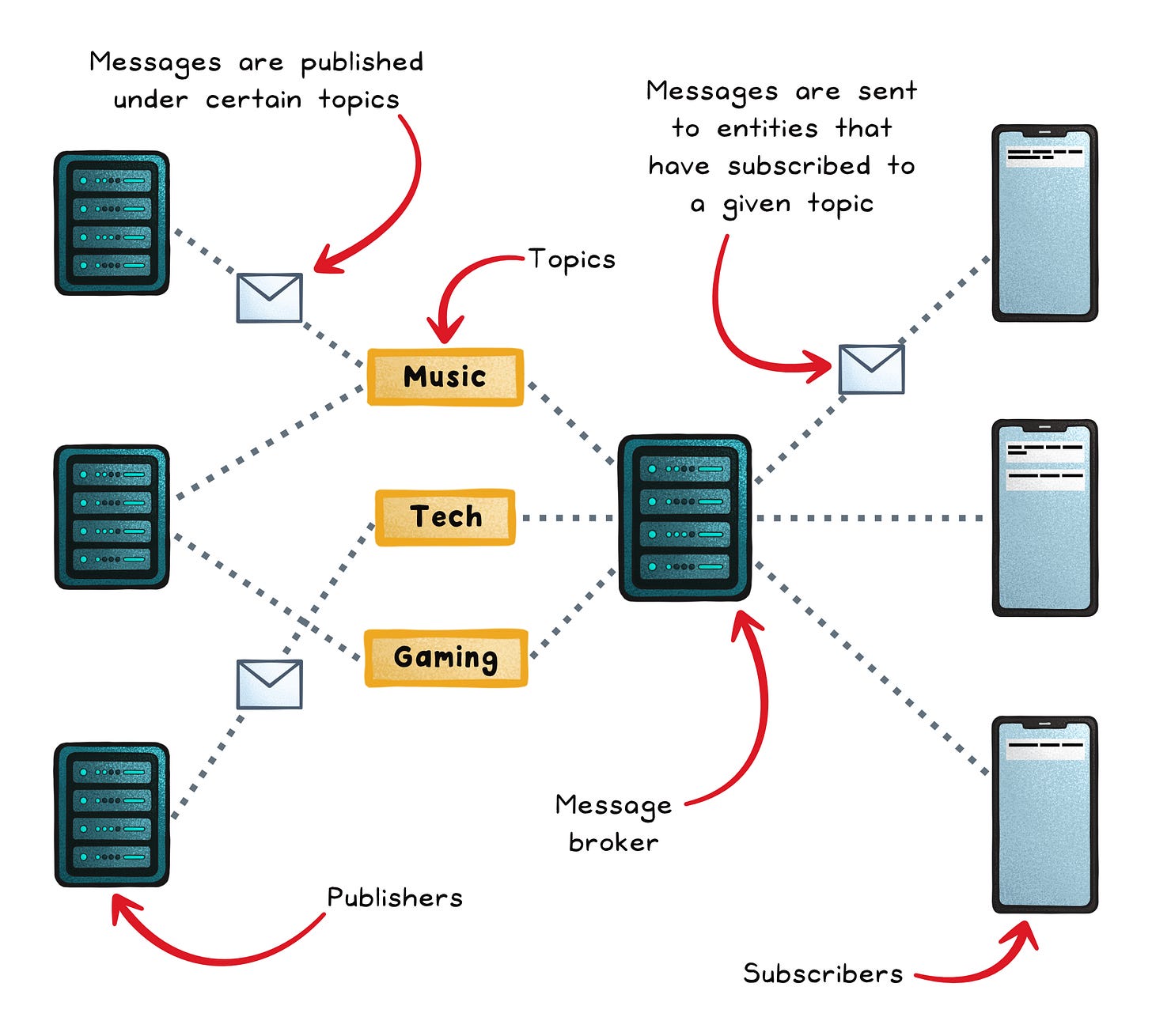

Most pub/sub setups have a broker (also called an event bus). Publishers send messages to the broker on a named topic/channel, and the broker routes a copy to every subscriber of that topic.

Key parts:

Publisher → Produces an event and publishes it to a topic.

Topic/Channel → The category label that subscribers use to filter what they receive.

Message broker → Tracks subscriptions and handles routing/buffering/filtering.

Subscriber → Consumes events for topics it subscribed to.

Two details that matter in real systems:

Push vs pull → Brokers may push events to subscribers, or let subscribers pull, depending on the implementation.

Transient vs durable → Some brokers store-and-forward (so offline subscribers can catch up), others only deliver to active subscribers.

Why Teams Reach for Pub/Sub

Pub/sub earns its popularity the moment a team feels how much friction it removes.

Instead of stitching services together with fragile chains of calls, you let events move through the system and let each component respond on its own terms.

That shift opens up a kind of freedom that’s hard to give up once you’ve experienced it.

It buys you that freedom in three ways:

Loose coupling → Publishers and subscribers don’t need to know about each other, so components evolve independently.

Async flow → Publishers don’t wait for subscribers to finish, so the system stays responsive and producers keep moving.

Fan-out scaling → One event triggers many independent workflows, and subscribers can scale out in parallel.

And you see the impact immediately.

A UserSignedUp event can kick off analytics, send a welcome email, run fraud checks, and sync the CRM; all without the signup service knowing or calling any of those systems.

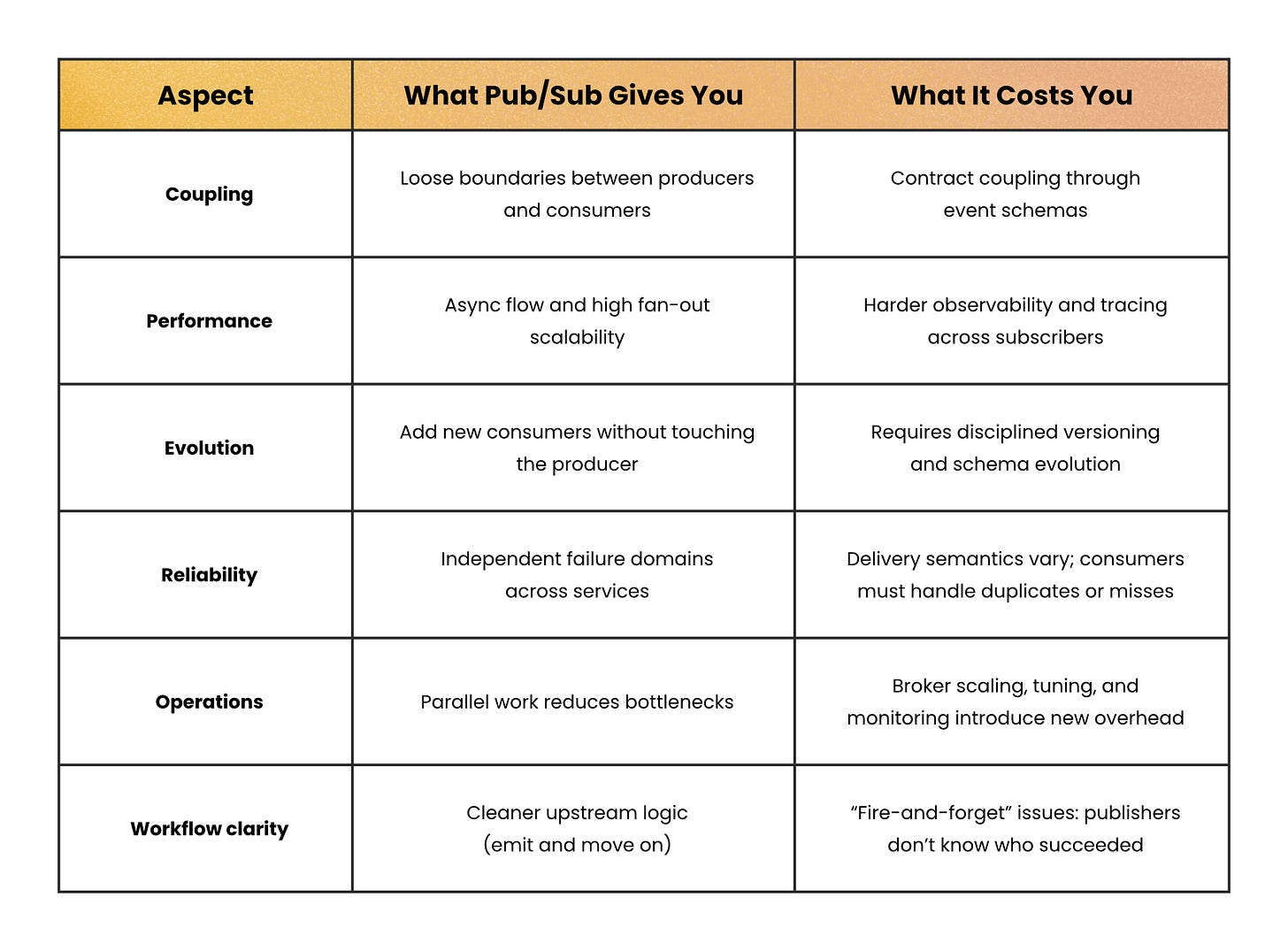

The Tradeoffs

Pub/sub feels like a breakthrough the first time you use it.

You publish an event, everything reacts in parallel, and the system suddenly looks cleaner and more scalable.

But the moment you move past the happy path, you start to see the tradeoffs that come with that freedom. The architecture gets simpler; the responsibilities shift somewhere else.

Here’s where the cracks start to show:

Debugging gets harder → Tracing “who reacted to what” is less obvious, so you need strong observability.

Delivery semantics vary → Many systems are at-least-once or at-most-once, so consumers must handle duplicates or missed messages.

Ordering is not guaranteed → Global ordering is difficult; you may only get ordering within a partition, or none at all.

Operational overhead is real → Running brokers, scaling subscribers, and tuning throughput adds complexity.

“Fire-and-forget” can bite you → Publishers typically only know whether the broker accepted the event; not whether any subscriber successfully processed it.

Schema still couples you → You remove service coupling, but you keep contract coupling via event shape/meaning.

In the end, pub/sub doesn’t fully erase complexity; it moves it.

Instead of wrestling with chains of downstream calls, you manage event contracts, consumer behavior, and the operational realities of the broker.

The system becomes more flexible, but you’ll need to carry the new responsibilities that come with that flexibility.

When to Use Pub/Sub

As systems grow, there’s a moment when direct calls stop being a convenience and start becoming a liability.

Pub/sub shines in that moment.

Use it when your system benefits from decoupled, asynchronous, one-to-many communication.

Where it works well:

One-to-many events → A single event triggers updates across multiple services/UI components.

High throughput workflows → Many tasks can run in parallel off the same event.

Rapid evolution → You expect to add new subscribers later without changing the service that emits the event.

Real-time feeds/notifications → One update fans out to many subscribers without polling.

When Not to Use It

But pub/sub isn’t magic; it works beautifully in the right context and poorly in the wrong one.

Don’t force pub/sub into problems that need the following:

Single dedicated recipient → Use a queue or direct call because fan-out isn’t needed.

Strict global ordering → Pub/sub ordering is hard; you’ll add complexity fast.

Immediate confirmation → If the workflow requires “did it succeed?” you need request/response or an explicit acknowledgment protocol.

Small/simple systems → Pub/sub can be overkill when a few components can just talk directly.

Best Practices

Pub/sub works best when you treat events as first-class APIs.

The architecture gives you room to move, but only if the contracts and operations are strong enough to support that freedom.

These practices help keep the system predictable as it grows:

Design clear event schemas → Define each field, its meaning, and its expected stability because consumers rely on your contract.

Version events thoughtfully → Add fields in a backward-compatible way and deprecate slowly so subscribers have time to adjust.

Make consumers idempotent → Handle duplicates safely because delivery semantics vary across brokers.

Keep events focused → Emit facts (“UserSignedUp”) rather than commands (“SendWelcomeEmail”) because facts allow many independent reactions.

Avoid leaking internal details → Publish stable domain-level events instead of exposing internals that might change as the system evolves.

Recap

Pub/sub gives you a different way to wire a system: publish once, react in many places.

It removes the tight coupling of direct calls and opens the door to parallel workflows, faster evolution, and cleaner boundaries between teams. But it also shifts complexity into event design, operations, and debugging.

In the end, pub/sub pays off when you embrace its power and its responsibilities.

👋 If you liked this post → Like + Restack + Share to help others learn system design.

Subscribe to get high-signal, visual, and simple-to-understand system design articles straight to your inbox: