How Rate Limiting Prevents Outages Before They Happen

(5 Minutes) | What Breaks Without Limits, Solutions, Best Practices, Risks, and Trade-Offs

Get our Architecture Patterns Playbook for FREE on newsletter signup. Plus, receive our System Design Handbook for FREE when it launches in February:

The First-Ever Free Kafka Tier is Finally Here

Presented by Aiven

Aiven just launched the first-ever Free Kafka Tier. A fully managed cluster you can spin up instantly. No credit card. Whether you need zero-cost environments, safe sandboxes, or frictionless PoC environments to test before pitching to management, it’s now finally here.

Rate Limiting Explained: How It Keeps Your System Fair and Fast

The best APIs don’t just respond fast; they stay calm under pressure.

That calm comes from invisible rules baked into every request: who can request, how often, and what happens when they exceed their turn.

Those rules are rate limits.

They don’t add new features or impress in demos, but they prevent the slow burns and overnight outages that cripple growth.

Without it, even the fastest API becomes fragile under real-world load.

What Breaks Without Limits

In every system, capacity has a ceiling.

Every connection, thread, database pool, and queue sits behind a finite resource limit. When requests surge past that threshold, your system starts to fail in nonlinear ways.

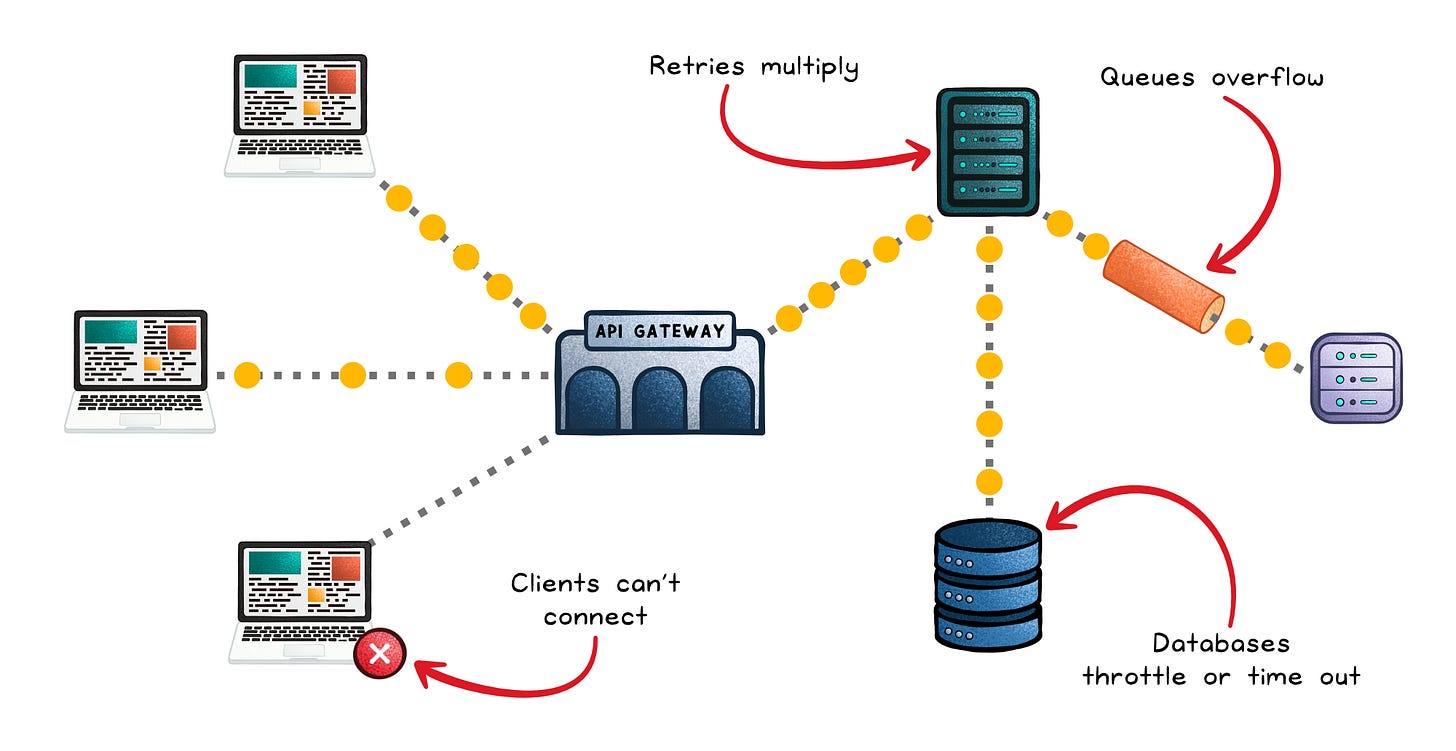

A single misbehaving client can trigger a chain reaction:

Connection pools fill up → Other clients can’t connect, causing cascading retries.

Queues overflow → Tasks drop or back up into upstream services.

Databases throttle or time out → The API appears “slow,” even when the root cause is overload.

Retries multiply → Latency spikes become traffic storms, pushing the system from slow to unreachable.

This isn’t just a traffic problem; it’s a fairness problem. Without controls, one client’s surge can starve everyone else.

And because distributed systems have shared dependencies (caches, message brokers, network bandwidth) the overload ripples far beyond the initial entry point.

That’s why rate limiting exists: not to make your system faster, but to keep it stable. It protects the critical path from bursts, bots, and bad loops by saying “not yet” before a single overloaded component turns into a full outage.

The Solution

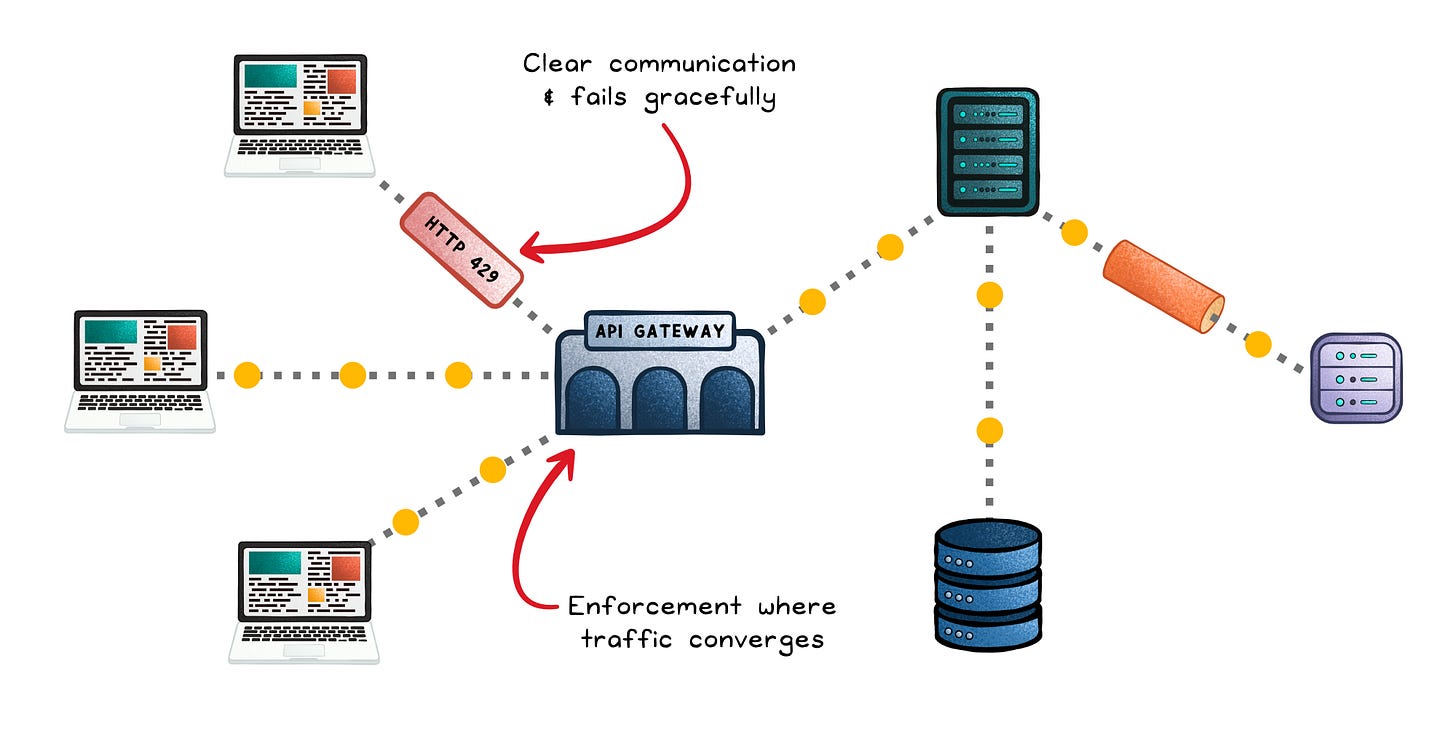

A rate limit is a contract between clients and your system. It says: “You can send this many requests in this much time, and no more.”

At its core, rate limiting combines a policy and an enforcement mechanism.

The policy defines what’s allowed; e.g. “100 requests per minute per user.”

The enforcement decides what to do when that policy is exceeded: delay, drop, or reject with an HTTP 429.

This enforcement usually lives where traffic converges:

→ API gateways (like NGINX, Envoy, or Kong) that see all incoming requests.

→ Edge proxies in front of microservices, ensuring fairness between clients.

→ Dedicated rate-limiter services using shared storage (like Redis or Memcached) to coordinate counts across multiple nodes.

The logic is simple: track how many actions a user (or IP, or key) has performed in a given time window, then decide whether to accept the next one.

But how that window is measured and updated matters. Different algorithms balance fairness, accuracy, and performance differently:

Token bucket → Each client has a bucket that fills with tokens at a steady rate. Every request spends one token. If tokens accumulate, the client can make short bursts; when empty, requests wait until the bucket refills.

Leaky bucket → Requests enter a queue and “leak” out at a fixed rate, creating a steady flow regardless of input spikes. It’s reliable for protecting downstream systems that can’t handle bursts, like payment or streaming services.

Fixed window → Each client gets a quota per fixed interval, e.g. 100 requests per minute. Once used, requests are blocked until the next window starts.

Sliding window → Sliding window tracks requests in a rolling time frame (e.g., the last 60 seconds) instead of resetting at fixed intervals. It evens out bursts and keeps limits consistent over time.

Once enforced, the system must also communicate limits clearly so clients can self-regulate. Standard headers like:

X-RateLimit-Limit→ total requests allowed in the windowX-RateLimit-Remaining→ how many remain before throttlingX-RateLimit-Reset→ when the count resetsRetry-After→ how long to wait after hitting the limit

Good APIs don’t just reject; they teach clients how to behave.

Best Practices

Good rate limiting balances protection and usability.

The goal isn’t to block traffic; it’s to keep systems reliable under real traffic.

Align limits with usage patterns → Study peak hours, burst sizes, and growth trends before setting thresholds. Adjust regularly as behavior changes.

Pick the right algorithm → Token bucket for bursts, leaky bucket for steady flow, fixed window for simplicity, sliding window for precision. Match the algorithm to your workload.

Layer your limits → Combine per-user, per-IP, and per-endpoint caps so one client or heavy operation can’t overwhelm others.

Use proven infrastructure → Gateways like NGINX, Kong, or Envoy, and datastores like Redis, handle rate limiting better than homegrown scripts.

Enforce at the edge → Place limiters where all traffic passes through: gateways, load balancers, or API proxies.

Fail gracefully → Return HTTP 429 “Too Many Requests” with a Retry-After header. Cool-off periods protect fairness without locking out good clients.

Monitor continuously → Track 429 rates, top offenders, and endpoint pressure. Adjust thresholds before overloads show up in latency charts.

Communicate clearly → Include headers like X-RateLimit-Limit, X-RateLimit-Remaining, and X-RateLimit-Reset so clients can self-throttle.

Encourage smart retries → Use exponential backoff with jitter to prevent the thundering herd effect (when many clients retry at once and flood the system again). Make endpoints idempotent so retries are safe.

Test and plan for scale → Stress-test your limiter, simulate failure modes, and ensure it defaults to safe limits (not open access) when things go wrong.

Risks & Trade-Offs

Rate limiting protects systems, but it adds its own friction.

The trick is managing that friction without hurting real users or performance.

Granularity vs overhead → Small windows catch spikes fast but raise processing cost; large windows are cheaper but let bursts slip through. The sweet spot balances responsiveness with efficiency.

Bursty traffic → Legitimate spikes can trip strict limits and block good users. Token buckets help, but too much burst tolerance risks short-term overload. Hybrid approaches often work best.

User experience → Every limit introduces friction. Set them too low, and users see errors; too high, and your system takes the hit. Different tiers (free vs. paid) help balance fairness and expectations.

Computational cost → Every limiter consumes CPU, memory, and bandwidth. Heavy algorithms like sliding windows can slow high-volume APIs, while shared counters (e.g., Redis) can become bottlenecks.

Distributed consistency → Enforcing a single limit across multiple servers is tricky. Each node only sees part of the traffic, so local counters can drift out of sync. Centralized stores (like Redis) keep counts consistent but add latency and potential bottlenecks. Large-scale systems often accept slight overages for the sake of throughput.

Fairness & circumvention → Uniform limits aren’t always fair. Users behind the same IP may share a quota unfairly, while attackers spread traffic across many IPs or accounts to dodge caps. Pair rate limits with IP reputation or CAPTCHAs.

The Takeaway

Rate limiting isn’t a constraint; it’s control.

It’s what turns unpredictable demand into predictable behavior and keeps systems fair when traffic isn’t.

The strongest systems don’t avoid limits; they design with limits in mind.

Because in the long run, reliability isn’t built by what you allow: it’s built by what you restrain.

👋 If you liked this post → Like + Restack + Share to help others learn system design.

Subscribe to get high-signal, visual, and simple-to-understand system design articles straight to your inbox: